UK

Common Name: Pine marten

Scientific Name: Martes martes

Fact

Pine martens prefer to live alone and only come together to breed in the summer.

About

The pine marten is one of Britain’s rarest mammals and is Critically Endangered in England and Wales. It was once was one of the most common carnivores in Britain, however, the population declined severely as a result of woodland loss, predator control, and hunting for fur, and had become extinct in large parts of the country by the early 20th century. Reforestation since the 20th century has improved habitat availability for pine martens and legal protection in the 1980s played a significant role in enabling the species to recover some of its former range in Scotland. However, this recovery has been slow and the species is still vulnerable.

Overview:

The pine marten is a Mustelid and a member of the weasel family. In the UK, the marten’s family includes the stoat, weasel, polecat, otter and badger. Globally, family members include wolverines, sea otters, tayras and honey badgers.

Lifespan:

Maximum life expectancy is approximately 10 years.

Habitat:

Pine martens prefer wooded areas with plenty of cover, where they make their dens and breeding nests in tree hollows and abandoned animal homes. They are, however, very adaptable and if woodland is scarce, the animals will occupy cliffs, crags, rocky mountain sides and occasionally the roof space of buildings.

When to spot:

January to December

Pine martens are mainly nocturnal, live at low density and are largely solitary. As a result, they are very difficult to see. They may be seen in the early and late hours of the day, especially in summer when they are most active. You may not spot one in the flesh, but discovering signs of them can be just as rewarding – look for footprints, scat and and lost fur in the undergrowth.

Diet:

Mainly voles and mice, but also rabbits, small birds, birds’ eggs, berries and insects.

Predators:

Foxes and golden eagles.

Fact

Each pine marten has a uniquely shaped bib, allowing individuals to be identified by the pattern.

How To Identify

Coming from the Mustelidae family, Pine martens are related to weasels, ferrets, polecats and otters. They look similar to these species, with dark brown fur and a pale yellow ‘bib’, round ears, long fluffy tail and long bodies. They are larger than many of their relatives - weighing about 1-2kg and 60-70cm long from nose to tail, roughly the size of a domestic cat. Males are around a third bigger than females.

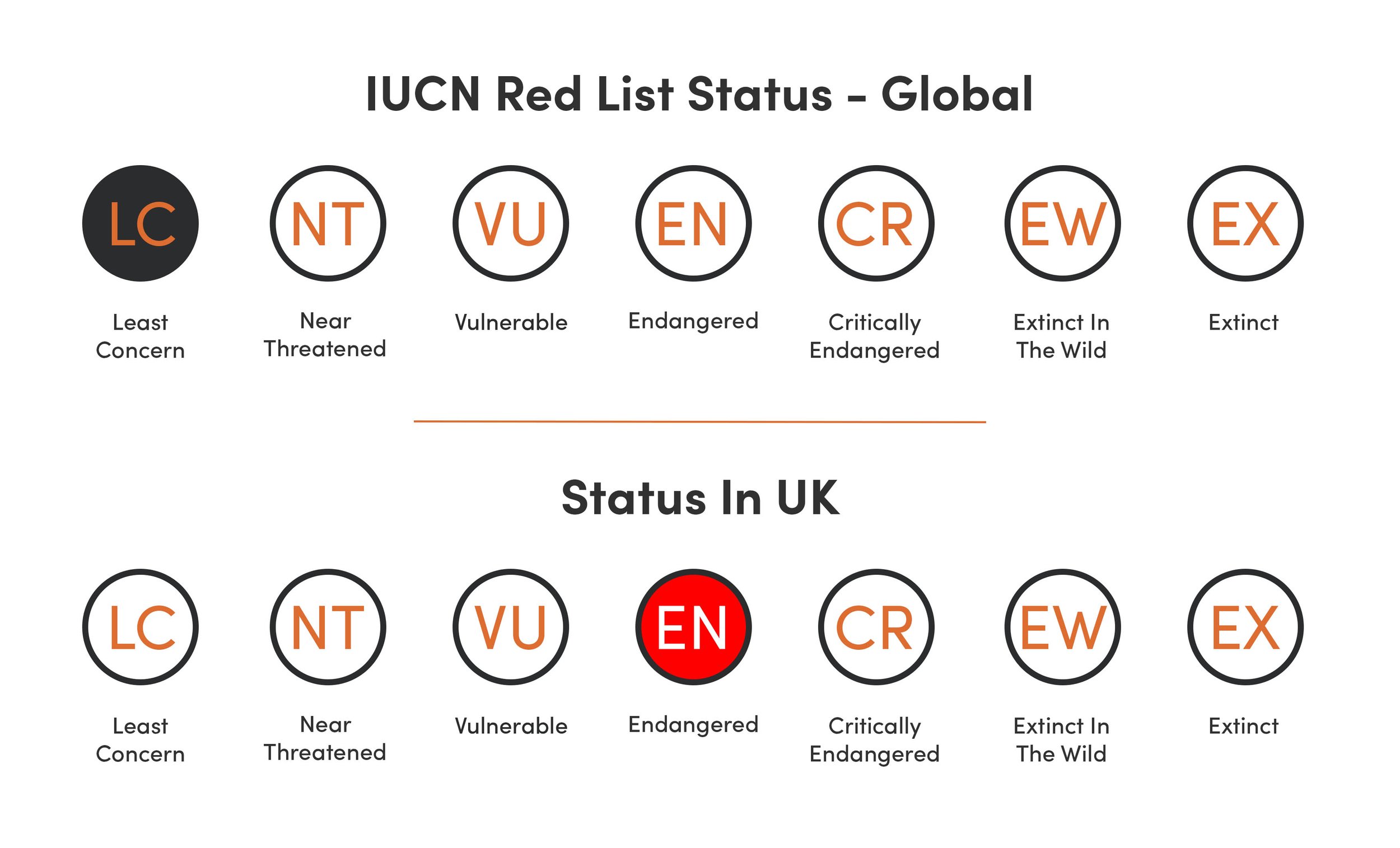

Vulnerability Status

IUCN Red List status: Least Concern

Country status: Critical

Protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. Priority Species under the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework

Population size: The pine marten remains one of the rarest native mammals in Great Britain, with a total population of around 3-4,000. Legal protection has allowed the Scottish population to grow, but the species remains critically endangered in England and Wales.

Approx. pine marten distribution in the UK

Threats

Despite legal protection, poisoned baits and traps, often set for hooded crows and foxes, still probably account for many marten deaths each year. Others are also shot at hen houses, and some are killed when mistaken for mink.

Key threats to species:

Habitat loss and fragmentation

Poor woodland management

By 1900, 95% of the woodland cover in the UK had been removed. The pine martens depend on this habitat for their arboreal life, and as a result the population saw a dramatic decline.

Importance of the species:

As native omnivores they play an important role in the balance of woodland ecosystems by controlling seasonally abundant species such as voles, fungi, berries and small birds.

Fact

Studies suggest that a pine marten influx could cause decreases in the non-native grey squirrel population, allowing the once-abundant red squirrels to move in.

Conservation Actions

Despite near extinction, pine marten populations remained in remote corners of Britain. Towards the end of the 1900s, the Scottish pine marten populations recovered, giving hope to their absence in England and Wales. Over the last century, woodland cover has doubled in England & Wales. Millions of trees have been planted to create new forests, and sustainable timber harvesting methods encouraged the maintenance of healthy, diverse woodlands. With the breeding success that can be seen in Scotland and woodland cover returning, there is hope for the future of the species in the UK.

In the summer of 2015, the first conclusive sighting of a pine marten in England in over a century was captured near the Welsh border in Shropshire.

Work is underway to boost the Welsh population; by 2017 a total of 51 pine martens had been translocated from Scotland and released in Wales.

What You Can Do To Help

If you see a pine marten in England or Wales, you can report it to the Vincent Wildlife Trust CLICK HERE.

You can adopt a pine marten through either the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust or Shropshire Wildlife Trust. Click the link for further details on what you will receive and how your donation will be used CLICK HERE.

Further Information

Click the title below for further information.

-

A report on official sightings of pine martens in the New Forest.

-

Details of the pine marten recovery projects managed by the Vincent Wildlife Trust.

Common Name: Natterjack toad

Scientific Name: Epidalea calamita

(previously Bufo calamita)

Fact

The male natterjack toads are the UK’s loudest amphibians and can be heard up to a mile away.

About

Overview:

The natterjack toad is smaller than the common toad only averaging 6-8cm in length and weighing 6-19g, whereas the common toad can measure up to 13cm in length.

Lifespan:

This amphibian breeds in warm, shallow pools on sandy heaths and dunes and coastal grazing marshes in just a handful of places in England and Scotland. They lay their spawn in single rows of eggs in 1-2m string-like formations. Similarly to a common toad, the natterjacks can live up to 10-15years.

Habitat:

Natterjacks are only found in three main habitat types in the UK: coastal sand dunes, upper salt marshes and lowland heathland. They are broadly scattered across eastern, southern and north-western England and the south-west of Scotland. Recently, reintroduction efforts have been seen in north Wales.

When to spot:

The natterjack toad is nocturnal and can be seen between March and September in the UK.

Diet:

They feed on woodlice, sand hoppers and other insects, as well as small marine invertebrates. Their ability to run allows them to catch their prey as they can run very fast over short distances.

Predators:

Foxes, otters, herons hedgehogs and gulls are all predators of the adult toad, but fish, birds, other amphibians and insect larvae are all threats to their spawn and tadpoles.

Fact

Female natterjack toads lay up to 7,500 eggs in a single clutch.

How To Identify

Natterjack toads are an olive-green colour and have a recognisable yellow stripe on their back. They tend to run instead of hop or walk, giving them the nickname of the ‘Running Toad’.

Image: © Tony Phelps

Vulnerability Status

IUCN Red List status: Least Concern - due to the large population sizes in Europe

Country status: Endangered

Population size: Natterjack toads are endemic to 17 European countries although populations are decreasing in all countries. In the UK there are approximately 4,000 adult natterjack toads in 60 sites.

Approximately 40% of all amphibian species are in decline according to the IUCN. The common frog, common toad and natterjack toad populations have all been reported as declining populations since the 1970s. The natterjack toads have declined by 70-80% since the beginning of the 20th century. One study in Ireland found that egg string production had declined by 23% over the last 14 years (-1.6%/year) despite conservation efforts.

Threats

Key threats to species:

Approx. natterjack toad distribution in the UK

Water pollution, changes in land management, loss of habitat, competition from invasive and non-invasive species as well as climate change have all contributed to the decline of natterjack toad populations. Natterjacks are highly sensitive and react to very small environmental changes - a thriving natterjack toad population is an indication of a healthy and well-functioning natural environment.

Spring droughts in the UK have become longer and more frequent, drying up water bodies early, which has led to poor breeding success in many amphibian species including the natterjack toad. Alongside this, agricultural and urban runoff has led to poor water quality in many breeding ponds and the abandonment of agricultural land surrounding the breeding grounds has led to unsuitable terrestrial vegetation for hunting.

Importance of the species:

Biodiversity is key to maintaining a healthy planet and a healthy home for all of Earth’s inhabitants. By keeping the natterjacks sand dune habitats intact we are afforded shelter from ocean storms, coastal erosion and coastal flooding.

The natterjack toads and many other toad, newt and frog species are great at controlling pests in gardens and crop fields. Ecosystem services such as this are essential to reducing the use of pesticides in agriculture.

Fact

Natterjack toads have full legal protection under UK law making it an offence to kill, injure, capture, disturb or sell them, or to damage or destroy their habitats.

Conservation Actions

Severe habitat loss in the last century has caused the natterjack toad population to significantly decline. As a result the natterjack toad is strictly protected by both British and European legislation (the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 and the Conservation (Natural Habitats &c.) Regulations, 1994). These laws make it an offence to kill, injure, capture or disturb populations, damage or destroy their habitat; or possess them or sell or trade them in any way. This applies to all stages of their life cycle.

Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust (ARC) was established in 1989 (rebranded from The Herpetological Conservation Trust in 2009) and have worked tirelessly to help protect and reintroduce many amphibian and reptile species. ARC provides advice to land managers, and the farming community about how they can support and create habitat for natterjack toads. ARC also manages and owns over 80 nature reserves across the UK.

The Gems in the Dunes project started in 2017 in the dunes of the Sefton Coast. Stretching from Southport to Seaforth, which form the largest undeveloped dune system in England. The Gems in the Dunes project was part of the Back from the Brink programme and has been working to manage local sand dune habitats and secure the future for many amphibians such as the natterjack toads. Since the start of the project hundreds of volunteers have been involved in recording natterjacks at breeding sites, alongside improving habitats, removing scrub and digging out natterjack pools. This does not only benefit the natterjack toad population but many other specialised animals and plants including the sand lizard.

What You Can Do To Help

You can volunteer and get involved with ARC research programmes surveying spawn, tadpoles and toadlets as well as monitoring habitats with natterjack toads.

Check out our Wildlife Gardening environmental calendar page to find out how simple changes in your garden can affect wildlife populations in the UK.

Another way to help protect amphibians is to slow down on the roads, especially in March when many amphibians are coming out of hibernation and might be crossing. If you're interested in finding out how limiting your speed can affect your environmental impact, have a look at our “The Silent Killer of the Climate Crisis” blog post.

Further Information

Click the title below for further information.

-

ARC was established in 2009 to provide a UK focus on all aspects of reptile and amphibian conservation. Visit their website to view the current projects and to learn more about other UK reptile and amphibian species.

-

Learn more about the Gems in the Dunes project.